|

After

the horrors of World War II, Theodor Adorno wrote that, it

is part of morality not to be at home in one's home. Yet as

a result of this extreme unsettledness some people decide

to stay at home literally to try to rebuild from the inside--even

at the moment when so many others decide to leave their homes.

Under these circumstances, home is most brazenly revealed

as inorganic; it is not a natural community that springs from

the ground or in the blood. As Adorno states elsewhere,whatever

is in the context of bourgeois delusion called nature, is

merely the scar of social mutilation...what passes for nature

in civilization is by its very substance furthest from all

nature, its own self-chosen object.

How have

the concepts of globalization and nationalism or radical fundamentalism--which

all can be viewed as utopian--related to each other in the

last ten years or so, and how has this relationship been playing

out in the past few months? In the midst of the unceasing

search for the selective homeland, or on the other hand, a

holistic global community, where is the home for critical

political formations?

Like the

medium of the web, home in the 20th century became increasingly

multiple. Whether or not home is migratory, it is certainly

constantly evolving through the play of imagination and also

everyday actions, as Benedict Anderson and May Joseph assert

respectively. Further, again like the internet, home is unstable.

It is aoristic, consisting of a multitude of forms without

clear bounds: departures, returns,enjoyment, longing, and

creative innovations.

(Quotes

from Adorno's Minima Moralia,

aphorisms 18 and 59)

The guests in New York:

Jonus Ademovic, architect from Mostar,

Bosnia, living in New York

May Joseph, performance theorist, New

York University

Drazen

Pantic, web media specialist and writer

Irit Rogoff, art historian, Goldsmith's

College, University of London

Sandra Sterle participated online from Zadar,

Croatia

The streamed discussion from Belgrade took

place in Dom Omladine in

collaboration with Center

for Contemporary Art, Belgrade. Thank you to them for

helping us to realize this project.

Milica and Branimir proposed

to participate in the project from their home in Belgrade.

Menu: Prebranac

(Balkan traditional bean dish), various salads, baklava, Bajadera

candy, red wine

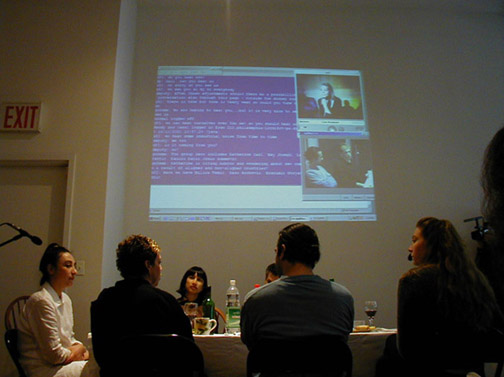

Introductions

around the table

Katherine:

First, Drazen, welcome to the table. Drazen has been behind

the scenes for every single streaming providing support and

mking it successful for everyone. So itís nice to have

him here at the table. Thank you Drazen. I just want to mention

that we can see the people in Belgrade on the screen;

Milica is in the middle. To her left is Branimir Stojanovic,

he is a theorist, and over on the right we see Aleksandar

Boskovic, he is an anthropologist, and he is from Belgrade.

He has been living in Johannesburg as a professor for some

time. He is going back and forth between Brazil. He has been

in Slovenia teaching. He teaches in a number of places. And

the translator, who is also in Belgrade is Svebor Midzic;

he will also contribute ideas to the conversation. And it

looks as though weíll be having the conversation through

typed chat since we are unfortunately not receiving any sound

from Belgrade.

Jonus:

I am from south of Bosnia, from Mostar, I am an architect

and artist. I have been living in New York for seven years.

I came as a refugee to America.

Irit:

I currently live in London. I am from Israel originally, educated

in Britain and in Germany, professionally trained in the United

States. I am a theorist of visual culture and most recently

my preoccupations have to do with what I call geographies,

which is the attempt to rewrite relations between subjects

and places, perhaps much in the name of what Katherine has

mentioned.

Danica:

I am a visual artist from Sarajevo, I live in Dusseldorf,

Germany. A lot of my work has to do with some kind of "collective

voice" and global issues. I would like to welcome you

to this go_HOME "last supper" on my behalf as well

as Sandra Sterle's, who will join us through the internet

from Zadar, Croatia.

May: I

originate from Tanzania. I've been doing a lot of work around

migration and citizenship and some of the issues that you

talk about here today are of interest to me, because some

issues have risen recently.

Drazen:

I came from Belgrade, and I have been here for the last three

years. I feel at home here, because it is so similar to Belgrade.

I used to work a little bit with B92, where I used to work

on the internet operation. And I am writing and creating internet

architecture basically around culture and globalization.

Katherine:

Something that I talked about a little bit with Milica was

whether there is a new community being created among these

formerly "non-aligned countries?" Now that the United

States is attempting to build a global alliance, is there

a new alignment in the world and are there critical political

voices taking issue with this global alliance? That is something

Branimir and Milica had been discussing. I would like to invite

people to raise questions and comments.

Jonus:

Katherine, when you said non-aligned, did you mean former

Yugoslavia or other countries of the world?

Katherine:

I meant the countries of the former Yugoslavia plus other

countries like Egypt, who were all in the 1970s considered

"non-aligned" with either of the cold war powers

of the United States or the Soviet Union.

Jonus:

Because we [the countries of the former Yugoslavia] were aligned

before the war.

Drazen:

Yes, we were something like a commonwealth.

Katherine:

Something that is interesting to consider, which Branimir

may bring up later, is his idea that at this time the United

States seems to be acting a lot like Milosevic was in the

1990s, in terms of forming a community that is very closed--now

this is on a global scale.

Jonus:

There is the Alpe-Adria region--Italy, Austria, and Slovenia--which

collaborated for long time even before Slovenia was a part

of the former Yugoslavia. That is very interesting for me

because we always hoped that in the former Yugoslavia once

you erase the borders of the state you would be free to form

your own identity. And then we have this unexpected emerging

of a secondary identity, which is a strange phenomenon for

me.

May: You

call regional identity secondary identity?

Jonus:

I don't know whether it is secondary or primary, but since

we are talking about nationalism, which I consider deals with

the national state in a political sense, it is the primary

identity.

Irit:

Do you think there is a sort of confusion around the three

terms: home, nation, and globalization. Have they begun to

be defined in opposition? In fact, I don't think they work

like that. Because, let's say the way globalization is working

right now is a kind of unholy alliance between someone called

General Musharaff and Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe and George

Bush in Washington and Ariel Sharon in Israel. What they have

in common is some kind of claim against terrorism. Whereas

in fact they--each and every one--are the regimes of unholy

terror. So I think it is terribly dangerous for us to fall

into the trap of saying that home, nation, and globalization

are antagonistic. They sustain each other all the time. Each

one is a necessary component for the development of the next.

In fact, it would probably be interesting to figure out how

people understand globalization from the personal perspective

of what one is doing, away from all of the large claims of

accessibility, constant circulation, internationalism, and

so on. How do you understand

globalization?

May: It

is a question that is quite hard at this time and point to

answer. Precisely because we have been so used to the language

of mobility, flows, hybridity, and nomadism. I am certainly

speaking from the vantage point of the United States. There

is, to me, an odd return to a moment that I associate with

early nation-state formation. I am thinking of Tanzania in

the '60s. Most of the non-aligned countries were decolonized

in the 20th century. So there was a lot of nation-building

in places like India and Tanzania. It was very much like not

having a home. Home was not an issue because it was never

possible--it wasn't available-- India was a new conception,

it was born in 1947 as a state. So the whole idea of home

was a new idea; and was one that was up for negotiation. How

it came to be was very violent. At that time the whole idea

of globalization was divided into two worlds: the cold war

and the third world system. So there were these two operating

logics that dissolved in 1989. For me, this whole idea of

globalization has three layers.

In fact,

globalization was an old phenomenon by the 10th century. There

have been elaborate migrations of peoples, movements of commodities

and of nomadic tribes for centuries. So globalization already

exists, in fact, in the 10th century, but in the 20th and

the 21th century it is defined in relation to passports and

citizenship.

Irit:

Globalization in the 10th century is a fact, but it is not

acknowledged because it happened in the East. The Western

European perception of knowledge is that it influences everything

else, and it is not influenced by much outside, despite the

fact as youíve said from the 10th century onwards,

people have been moving across continents and oceans. So I

think globalization is not really about what is happening

today. It is more about the willingness to acknowledge that

shifts have occurred in the relations between places and knowledge.

For me it is much more a consciousness shift than an economic

shift or the free-floating circulation of commodities.

May: But

the question that I have is how does citizenship fit in? Because

one of the things that globalization madedifficult was the

legal or illegal state of being. You know, the difficulty

of being in a state where one was not born, and on the other

hand, the right to be in a state by definition because one

is Serbian or Croatian or a particular ethnicity.

Drazen:

The thing with globalization is that telecommunication, the

internet, and satellites have opened this public space providing

fast and free circulation of informatiom.

Irit:

Yes, you have all the apparatus to communicate but the question

is who and what is allowed to circulate freely and who is

kept absolutely bound.

Katherine: I am sorry to interrupt

but Sandra has joined us online from Zadar. And also in Belgrade

they were wondering about your comment, Jonus, about the alliance

of the formerly non-aligned countries being something natural,

being something organic. Could you elaborate a little more

on that?

Jonus: I didn't mean non-aligned

countries. I meant more the alliance of space, for example

as Iíve already mentioned Alpe-Adria.

Katherine: In the chat,

Sandra and Dan mention that,"ìpeople change alliances

very often nowadays, and this is somehow different, but not

very different from politics: it is a question of different

kinds of identities. Mentioning primary or secondary identity,

there are different alliances of belonging, different communities."

But I think they are also pointing out the political situation

at the moment. People are switching alliances for political

reasons. They continue, "Probably our world is becoming

much more fragile." They are asking from

Belgrade, "is there any space between global capital

flow/corporate spaces and Islamic fundamentalism--is there

any space between those two and how does this function?"

Drazen: There is very sharp

line or boundry between those two.

Katherine: Milica Tomic and

Branimir Stojanovic from Belgrade are asking us to listen

to their stream from Dom Omladine. There is no sound coming,

so weíll communicate by typing.

Fritzie: I don't think I can

deal with this.

Katherine: (reading

from the screen "I think we tend to see the current historical

moment as the defining one. I think this is a great oversimplification."

Jonus: Thinking about globalization

in terms of flow of capital and preservation of local economy

is interesting to me. Let me tell you this funny story about

McDonald's in Sarajevo. After the Olympic games, McDonald's

wanted to open a store on Bascarsija (old and famous part

of Sarajevo) and the marketing team reported that they couldn't

compete with Bascarsija traditional restaurants because no

one would eat McDonald's there. Because of the war the opening

of McDonald's was delayed and about four years ago they thought

they would move to another part of the city near the art academy

and theatre district. The marketing department concluded that

there would be no profit at that location either because artists

and students certainly don't eat McDonald's food and hate

the whole idea that it represents. So finally a year ago McDonaldís

opened a store in the suburb of Sarajevo, the so-called new

part of the city "Alipasino polje" where there are

no local traditional stores, and nobody cares. Iíve

recently read in the Village Voice

that the best burger in New York City is in this tiny, tiny

Bosnian place in Queens. There are even no tables, but it

is said to make the best burgers in the city. These two stories

was some strange, perverse dislocation for me. This proves

the notion that McDonald's would have failed on Bascarsija.

|

|

|

Drazen: During the bombing

of Belgrade, in order to survive the McDonald's there had

the staff wear hats that were just like the "Sajkaca,"

the traditional Serbian soldier cap from World War I that

is some kind of national symbol.

Katherine: I'd be interested

to hear people's comments about the opposite effect of exporting

local culture out into a wider global realm. For example,

looking at local pop cultural forms that are not coming from

Hollywood, but end up being marketed and exported.

Irit: Last year I went to

see the big pop art exhibition in Paris, one of those flamboyant

exhibitions that Centre Pompidou puts on. One of the things

that I realized was that the Indian connection was completely

lost in the history of pop art. There is a way, for example

that Indian culture circulates in the late '60s through music

and through pop art--decorations and clothing--that is absolutely

not acknowledged. One thing that we are exceptionally bad

at is that kind of acknowledgement of cultural circulation.

It was George Harison dying last week that certainly made

me think of these incredible connections. For the whole late

'60s India is everywhere. And that is circulation. I think

the ability to break this kind of self-sufficient model for

the West is important and to recognize that we are shaped

and not just shape.

May: One of the examples of

globalization that I give to my students is to take them to

the world music section of Tower Records. I do that because

I work in the field of performance and the cultural circulation

of performance. It has always struck me that postmodernism,

and before this the avant-garde, was always available as part

of the identity of the West (I see this very broadly as Europe

and the United States). But the western view of the identity

of Japan or Taiwan or India is always one exclusively of traditional

forms and high culture, not pop culture. I was part of the

avant-garde movements back in India, which experimented with

ideas that have come out as international influences. We incorporated

Indian influences as well and in theatre. But that was not

the sort of theatre that would gain visibility, that would

circulate, to come to New York. For instance, when Brooklyn

Academy of Music is looking for a representation of African

performance--in other words South Africa--they'll get a national

theatre group and to represent India they bring the National

Theatre. When it comes to interesting performance coming from

Europe one looks for the extreme avant-garde. So it is always

interesting for me that in globalization you reach a kind

of a limit point. There is very interesting East African form

of music, that was Arabic plus incorporating Cuban forms,

but these are the forms that don't circulate because they

don't fit into the US notion of what is African music. I guess,

what I am saying is that globalization produces a kind of

localness. For instance, American jazz musicians, working

in experimental forms, can go to India or Africa and pick

an artist to do fusion with, but if an artist from Africa

or India wants to apply for something in the United States,

they have to prove they work in a pure form, A traditional

form that fits into the recognizable category.

Irit: These recognizable categories

and the cultures that produce them are considered sacred by

the West. They are what Levi-Strauss called "sacred zones."

You keep certain places in the world as sacred zones--it is

an manipulative exercise of Western power.

Katherine: Milica and the

people in Belgrade are were wondering if we have questions

for her. Could we pose questions about her work or about the

thinking that is currently going on in Belgrade?

Irit: One of the things that comes to my mind

when I think about Milica's work is that she creates an intertextuality

of trauma. Her work, "I am Milica Tomic" accomplishes this.

Her creation of trauma is linked to the structure of trauma

and not to the detail or local specific experience of trauma.

We actually have to find the language in which each of those

traumas can speak to one another, in a sort of intertextuality.

I'd like to know Milica, what do you think? And also I am

really sorry, that I can't hear

you.

Katherine: There is some chat dialogue

in Serbo-Croatian between Sandra and B92, which is great.

The people in Belgrade are very concerned, they are feeling

cut off. They can see

us but they can't hear us. They are asking if we can see

them.

Jonus: It is strange with

this delay...

May: This delay actually describes

one of the dilemmas in globalization discourse as well. In

the third world we always have tradition, but we don't have

modernity because our modernity is always viewed as a repetition

of what has already happened in the West. That is the delay.

Modernity experienced in the so-called third world is always

an echo of Western modernity and not something else that is

new. The whole question of other kinds of modernity really

did come up in very difficult ways with the current situation.

The United States has always considered Muslims part of their

community, but Islam was somehow outside the United States.

We have a large Muslim community in the United States and

now with this whole event we have very comlicated questions

about who is a citizen, even if you have had citizenship for

four generations, like Palestinian-Americans.

Irit: I think that the United

States has very serious Christian fundamentalism and that

is not perceived in the same way as Islamic fundamentalism,

because the underlying concern is not about fundamentalism

but about Islam, and it is about geopolitical interest. For

example the conversation or conjuctions between something

called Christian fundamentalism and something called Islamic

fundamentalism is not brought up; that is not recognized at

all; that is out of question.

May: Thank you for talking

about Christian fundamentalism. It is a very difficult time

to talk about this...it is a very depressing time.

Katherine: I am so sorry,

but I really do need to interrupt because in Belgrade they

are having a parallel

conversation going on at the moment, and they are talking

about copyrights. Aleksandar is an anarchist, and he is very

concerned about copyrights and ownership in relation to nationalism

and globalization. The question is about what nationalism

is and how it is related to ownership. Then Branimir says,"the

nation is a19th-century problem, not a modern problem. the

nation died in concentration camps during the Word War II."

Jonus: He is talking about

delay, we formed in our world some kind of delayed process

of forming nation states...

Katherine: He may also be

saying something about the notion of home, or home as nation,

being suspect.

Irit: That goes back to the

way in which politics and positions are always written under

the sign of the nation-states, not under the fact of internal

conflict with the nation state. Globalization becomes a lot

of nation states. And that is why I am sort of suspicious

of the notion of home, because home is some kind of attempt

at refuge from the nation-state. There is no refuge. It is

absolutely pointless. My worry about home is that it always

becomes a place where you can drop out. I think it is sentimental

because of this notion of dropping out.

May: There is actually no

core to what we call home; it is like an onion. There are

different layers that we experience, which create forms of

belonging, and they shift, and traumatise, and they mutate.

This all makes up home, but there is no singular essence of

home. For example my accent changes according to where I am.

When I am in India, my accent is more Indian, when I am in

Africa, my accent is more African, English, etc.

Jonus: I think that home is

a point from which circles of family, friends, neigbourhood,

city, state, and world emerge. During the war in my hometown,

Mostar, the first two circles of family and neigborhood broke

down. When this happened it was much worse than anybody could

ever imagine. When I read the letter

from Milica and Branimir, who described themselves as immigrants

within their own city and country, I was thinking about this

condition and their experience. Maybe they feel that their

primary circle, their family, friends, neighbors, or their

home is intact, but there is this vacuum between state and

the world. The world abandoned them just as their state abandoned

them.

Katherine: The participants in Belgrade are

asking you if you have a home, Jonus.

Jonus: I have a home as long as my parents

are alive.

Danica:

Nationalism and Globalization or Pleasure of Drinking Water

Special

thanks to Jonus Ademovic for bringing 3 bottles of mineral

water, from 3 different sources (Sarajevska Mineralna Voda

from Bosnia, Knjaz Milos from Serbia, and Radenska from Slovenia),

bought in Astoria, Queens, New York.

|